J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(5):22-24.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(5):22-24.

A Case Report of Idiopathic Eruptive Macular Hyperpigmentation, An Uncommon Entity

Dear Editor:

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP) is a rare benign pigmentary disorder that affects younger individuals.1 It presents as asymptomatic brown-black macules or patches over the trunk and proximal extremities, occasionally affecting the face.2 They occur without any preceding inflammation or drug exposure. It is essential to perform a biopsy to achieve the correct diagnosis. Differentials include erythema dyschromicum perstans, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, urticaria pigmentosa, lichen planus pigmentosus, and fixed drug eruption. IEMP does not require treatment as it tends to resolve spontaneously over several months to years, without scarring or residual pigmentation. Here, we discuss a case of a 13-year-old girl presenting with asymptomatic hyperpigmented macules over her trunk and limbs.

A 13-year-old healthy female presented with two years of multiple hyperpigmented macules over the body and limbs, sparing the face. They were increasing in numbers but were asymptomatic. There was no preceding medication or contactants used. On examination, there were multiple non-velvety and non-scaly faint hyperpigmented brown macules. Her oral mucosa was clear and examination of her nails was unremarkable. Darier’s sign was absent.

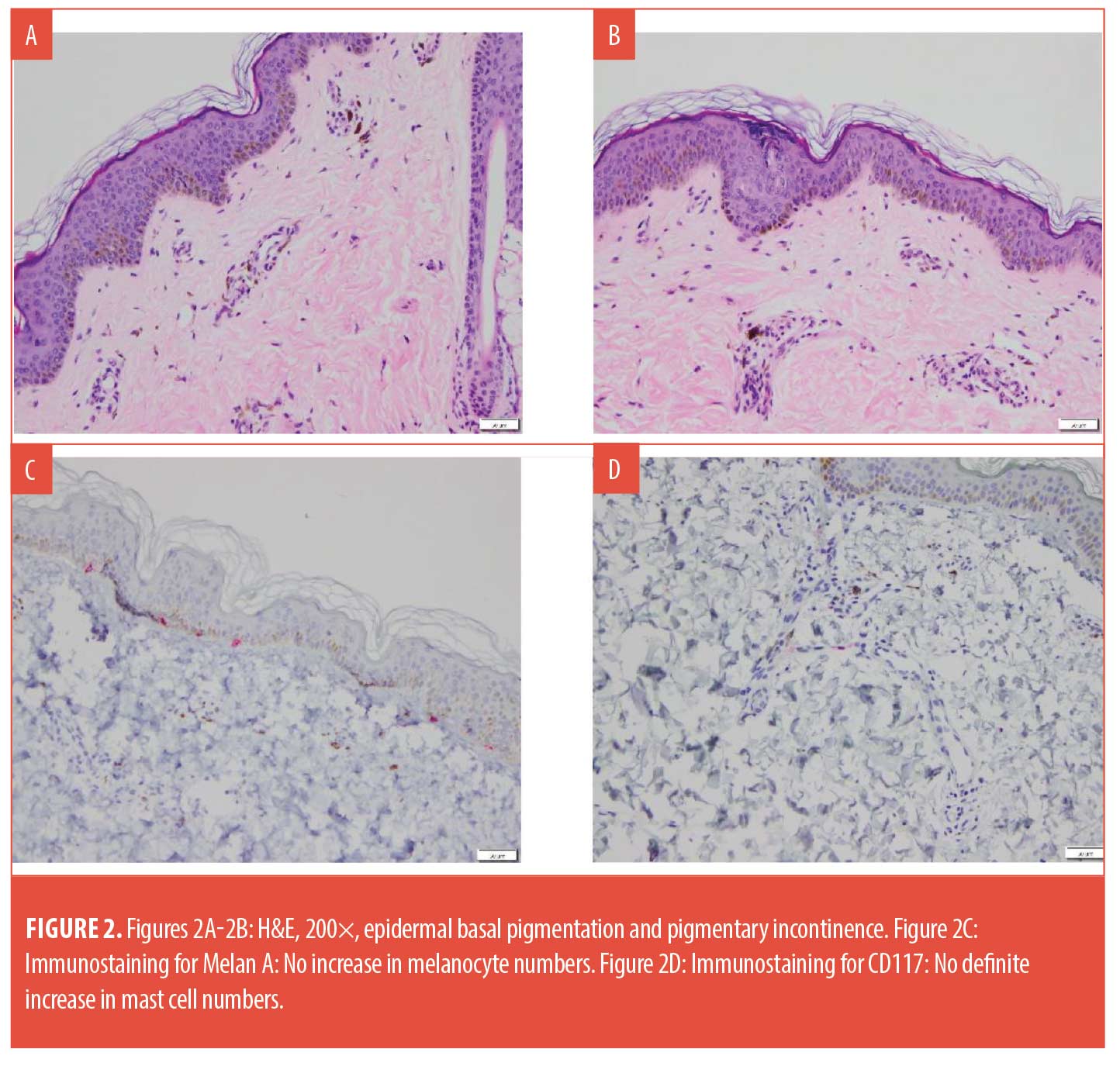

Histology revealed increased epidermal basal pigmentation and prominent pigmentary incontinence. There was no evidence of lichenoid inflammation, interface vacuolar change, significant spongiosis, or dermal eosinophils. While there was some epidermal undulation, papillomatosis was not observed. Melanocyte and mast cell numbers were not increased.

IEMP is an uncommon entity affecting the young and is often difficult to diagnose. Sanz de Galdeano et al3 suggested the following five criteria for the diagnosis of IEMP:

- Eruption of brownish-black discrete, non-confluent asymptomatic macules involving the neck, trunk and proximal extremities in children and adolescents.

- Absence of any preceding inflammatory lesions.

- No previous drug exposure.

- Basal cell hyperpigmentation of the epidermis with dermal melanophages without any basal cell damage or lichenoid infiltrate.

- Normal mast cell counts.

There are reports suggesting that IEMP may be an eruptive variant of acanthosis nigricans.2,4 However, our patient’s clinical and histological features did not resemble that of acanthosis nigricans. Some authors state that an additional criterion for IEMP is that it does not require treatment and should resolve spontaneously over several months to years without scarring or residual pigmentation.5 A biopsy is essential to clinch the correct diagnosis, allowing clinicians to accurately counsel parents and patients on the self-resolving nature of the disease and avoid unnecessary treatment.

With regard,

Heng Li Wei, MBBS; Wong Soon Boon Justin, PhD; and Liau Meiqi May, MRCP

Affiliations. Dr. Heng is with the Department of Medicine at the National University Health System in Singapore. Dr. Wong is with Department of Pathology at the National University Health System in Singapore. Dr. Liau is with the Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine at the National University Health System in Singapore.

Keywords. Idiopathic eruptive macular hyperpigmentation, pigmentary disorder, benign, pediatrics

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Jang KA, Choi JH, Sung KS et al. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: report of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(2 Suppl):351–353.

- Vasani RJ. Idiopathic Eruptive Macular Pigmentation – Uncommon Presentation of an Uncommon Condition. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63(5):409–411.

- Sanz de Galdeano C, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: report of five patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13(4):274–277.

- Misri RR, Khurana VK, Thole AV, et al. Idiopathic Eruptive Macular Pigmentation with Papillomatosis: An Unfamiliar Entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(5):581.

- Trcko K, Marko PB, Miljković J. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2005;14(1):30–34.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(5):22-24.

Weekly Pulse Dosing of Tetracyclines for Treatment of Acne

Dear Editor:

Tetracyclines are a key component of acne treatment, with standard daily or twice daily dosing.1 The most recent AAD guidelines of care in the management of acne vulgaris recommends continued maintenance therapy of oral antibiotics until clinical improvement allows discontinuation of the drug and encourages limiting use to the shortest duration possible.1 However, follow up appointments are often scheduled 1 to 3 months later, meaning that patients may be continuing the tetracycline antibiotic for a longer period than needed. This is potentially problematic given increasing antibiotic resistance, as well as drug side effects such as gastrointestinal upset and photosensitivity.1 Additionally, longer courses of antibiotics may lead to higher potential for medication non-adherence.

Pulse dosing is commonly used in the treatment of onychomycosis to reduce the risk of side effects, with high efficacy.2 Likewise, pulse dosing of azithromycin, a second-line antibiotic agent, has been explored for treating acne vulgaris, with success in some studies.3 Dosing regimens in previous studies have varied. Interestingly, one small study noted no difference between daily dosing for four/five days per month and three times weekly dosing over a three-month period.4

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no published studies exploring pulse dosing with tetracyclines in the treatment of acne. Over the last 20 years, one of the authors, has observed great efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction by instructing patients with inflammatory acne to take doxycycline or minocycline twice daily for 7 to 10 days when having moderate-to-severe flares (in combination with a topical retinoid and benzoyl peroxide-clindamycin gel). This utilizes a pulse dosing strategy on an as needed basis rather than having the patient continually take the oral antibiotic daily until the next follow-up appointment.

The literature highlights that more than half of Cutibacterium acnes strains are resistant to antibiotics.5 Erythromycin shows the highest resistance rates followed by clindamycin and doxycycline.5 This is concerning given that antibiotic resistant pathogens are emerging faster than new antibiotics can be developed.5 Prolonged and inappropriate use of antibiotics plays a large role in the development of antibiotic resistance;5 consequently, weekly pulse dosing of oral tetracyclines for flares could be an effective strategy for addressing this public health issue for both men and, especially, women who experience acne surges during their menstruation. Moreover, this strategy may lead to greater patient satisfaction and compliance given that it actively involves patients by requiring them to evaluate the severity of their acne and the need for the oral antibiotic. Additionally, taking the oral antibiotic for a week is more convenient than taking it daily for a few months. In order to assist patients with assessing the need to take the oral antibiotic, the author who employs this strategy advises patients to take the oral antibiotic when 10 or more inflammatory acne lesions are present and to forgo usage when less than 10 lesions are present.

We encourage future studies exploring pulse dosing of oral antibiotics in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris to assess treatment outcomes, safety (including rates of antibiotic resistance), and cost-effectiveness.

With regard,

Amylee Martin, MD; Magnus To, MD; and Ethan Nguyen, MD

Keywords. Acne vulgaris, antibiotic, tetracycline, resistance, adherence, pulse therapy

Affiliations. All authors are with Raincross Dermatology & Cosmetic Surgery in Riverside, California.

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 May;74(5):945–973.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: Treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80(4):853–867.

- Kim JE, Park AY, Lee SY, et al. Comparison of the Efficacy of Azithromycin Versus Doxycycline in Acne Vulgaris: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Dermatol. 2018 Aug;30(4):417–426.

- Naieni FF, Akrami H. Comparison of three different regimens of oral azithromycin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:255–257

- Shah RA, Hsu JI, Patel RR, et al. Antibiotic resistance in dermatology: The scope of the problem and strategies to address it. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 Jun;86(6):1337–1345.

Anti-COVID-19 Face Masks and Perioral Dermatitis

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(5):22-24.

Dear Editor:

Perioral dermatitis (POD) is a papular-vesicular-pustular disease, with a chronic clinical course, of the perioral area. It occurs mainly in middle-aged females. It is often caused by topical corticosteroids, although cosmetics and toothpastes containing chlorine or fluorine may sometimes be responsible for the disease. To our knowledge, only two articles have been published about POD associated with or caused by anti-COVID-19 face masks.1,2 We present the results of a study carried out in the metropolitan area of Milan, Italy, on POD before and during COVID-19 pandemic.

In the period October–December 2019, we observed an average of 14 patients per month with POD. From May 2020 to December 2021 we observed an average of 24 patients per month with POD; however, from October to December 2021, the average was 32 patients per month, i.e., more than twice in comparison with the period October–December 2019. All patients were females, except one male, who wore an anti-COVID-19 face mask for 6 to 12 hours per day. There were no differences about the type of face masks (surgical or cloth or N95 masks). It is worthy of note that approximately 25 percent of these patients were not affected by POD before the COVID-19 pandemic: anti-COVID-19 face mask can therefore be considered as a predisposing factor for POD. Furthermore, in our patients POD was observed almost exclusively in the skin underneath the masks. Face masks induce an increase of the temperature of the face, with subsequent abnormalities of microbiota (proliferation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and/or Fusobacteria spp. and/or Demodex folliculorum) and permeability of skin barrier.3 In conclusion, POD is an additional dermatitis of the face that, like acne, rosacea, and seborrheic dermatitis, can be caused or worsened by the frequent use of anti-COVID-19 face masks.2,4,5

With regard,

Stefano Veraldi, MD, PhD; Maria Alessandra Mattioli, MD, and Gianluca Nazzaro, MD

Keywords. COVID-19 face masks, perioral dermatitis

Affiliations. Drs. Veraldi and Mattioli are with the Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, at the Università degli Studi di Milano in Milan, Italy. Dr. Nazzaro is with the Dermatology Unit at Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, in Milan, Italy.

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. The authors report no disclosures relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Olisova OY, Teplyuk NP, Grekova EV, et al. Dermatoses caused by face mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021; 35: e738–e741.

- Niesert AC, Oppel EM, Nellessen T, et al. “Face mask dermatitis” due to compulsory facial masks during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: data from 550 health care and non-health care workers in Germany. Eur J Dermatol. 2021; 31: 199–204.

- Teo WL. The “Maskne” microbiome – pathophysiology and therapeutics. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:799–809.

- Searle T, Ali FR, Al-Niaimi F. Identifying and addressing “Maskne” in clinical practice. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14589.

- Veraldi S, Angileri L, Barbareschi M. Seborrheic dermatitis and anti-COVID-19 masks. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:2464–2465.