J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(6):42–48.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(6):42–48.

by Vanina L. Taliercio, MD, MS; Ashley M. Snyder, MPH;Lisa B. Webber, BS; Adelheid U. Langner, BS; Bianca E. Rich, BS; Abram P. Beshay, MD;Dominik Ose, MPH, DrPH; Joshua E. Biber, MS, MBA; Rachel Hess, MD, MS; Jamie L. W. Rhoads, MD, MS; and Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD

Drs. Taliercio, Beshay, Rhoads, and Secrest, Ms. Snyder, and Ms. Webber are with the Department of Dermatology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Ms. Langner and Ms. Rich are with the School of Medicine at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Mr. Ose is with the Department of Family and Preventative Medicine at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Drs. Hess and Secrest, Ms. Snyder, and Mr. Biber are with the Department of Population Health Sciences at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Dr. Hess is also with the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

FUNDING: This research project was funded by a Discovery Grant from the National Psoriasis Foundation awarded to Dr. Secrest. Dr. Secrest is also supported by a Public Health Career Development Award from the Dermatology Foundation.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Pruritus is the most common symptom of psoriasis, with a significant impact on patient quality of life. In spite of this, the severity, persistence, and overall impact of itchiness has only been rarely formally assessed during standard psoriasis clinic visits.

Objectives. We sought to understand the far-reaching impacts of itchiness on the lives of those with psoriasis and their families.

Methods. We conducted a qualitative study with five focus groups and 10 semi-structured interviews from August 2018 to January 2019. We enrolled 25 individuals with a diagnosis of at least moderate plaque psoriasis and 11 family members (primarily significant others). Views and experiences were analyzed thematically via content analysis.

Results. Itchiness considerably impacts those with plaque psoriasis and their families. Our narrative analysis produced three main themes relating to itchiness: the triggers of itchiness, including climate, emotions, and behaviors; the physical consequences of itchiness, including disruption of emotional well-being, sleep disturbance, and daily activities; and the prevention and treatment strategies used to alleviate itchiness.

Conclusion. Itchiness impacts the quality of life in those with psoriasis and their family members. We strongly urge clinicians to inquire about and monitor the severity and impact of itchiness in psoriasis patients.

Keywords: Psoriasis, itchiness, pruritus, qualitative analysis, relationships, quality of life, therapeutics, focus groups, biologics, symptoms, triggers, prevention

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting 2 to 3 percent of the American population.1,2 Psoriasis mainly affects the skin and joints and is associated with comorbidities like cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. Psychosocial comorbidities, including psychological distress, stigmatization, social isolation, and physical dysfunction, are also well recognized by the literature.3–5

The prevalence of itchiness in psoriasis is greater than 70 percent.6–9 Dermatology textbooks and residency programs identify itchiness as a common symptom of psoriasis, but the debilitating nature of this symptom is often not discussed. Recent work on the quality of life of psoriasis has identified itchiness as a critical negative factor of overall well-being.6,10

Despite its near ubiquitous presence in psoriasis, the degree of itchiness and its consequences on patients and their families is incompletely assessed in daily practice, if at all. The severity of itchiness is not strongly correlated with overall clinical disease severity.6,11,12 To date, most studies on itchiness have been quantitative, lacking a qualitative aspect when assessing patients’ experiences with itchiness. Our study aims to capture the experiences of patients suffering with this symptom and to understand the impact of itchiness on quality of life and relationships in both patients with psoriasis and their loved ones.

Methods

Study design. Using the skills of a trained facilitator (D. O.), we carried out five focus groups and 10 semi-structured one-on-one interviews with patients with psoriasis and their family members between August 2018 and January 2019. The study was approved by the University of Utah institutional review board (#102556).

Participants and setting. Participant numbers were determined a priori and selected to provide a sample size large enough to reach thematic saturation. Of 61 individuals invited to participate, 36 accepted, including 25 patients with psoriasis and 11 family members. We reached thematic saturation from these groups, whereupon no further new information was gained. All participants were at least 18 years of age, spoke English, and were recruited from the University of Utah Health Psoriasis Clinic either through referring physicians or by review of the electronic medical record. Those identified were then called on the phone and invited to participate. To broaden the representativeness of participants, we selected patients of varying ages, sexes, sexual orientations, and current disease status (ranging from no active disease [on treatment] to severe disease). The family members recruited were ideally a spouse/significant other (n=9), but also included two parents, one adult daughter, and one adult sister—each of whom lived under the same roof as their loved one with psoriasis.

All participants provided verbal consent for study inclusion to one of the investigators (V. L. T.) during recruitment and were subsequently provided with written consent forms to sign and the opportunity to ask questions prior to starting the focus group/interview. Anonymity and confidentiality were preserved throughout the study. All psoriasis patients had received a diagnosis of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and many were exhibiting good disease control at the time of participation.

Data collection. Two lead investigators with experience in qualitative methods and psoriasis developed a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions, intending to explore participants’ experiences with itchiness, pain, sleep quality, and personal relationships due to psoriasis in greater depth. Themes and interview questions were based on theoretical considerations, expert discussions, and an extensive literature review in accordance with the principle of theory-driven qualitative research. Based on Carl Rogers’ person-centered approach,13 the investigators used an integrative model of patient-centeredness to guide the development of the guidelines.14

All focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews lasted 15 to 35 minutes, and focus groups lasted 60 to 70 minutes. Sociodemographic data were collected via paper survey.

Data analysis. Qualitative content analysis was centered around the following general request: “Tell me about the itchiness of your (or your loved one’s) psoriasis” (Table 1). Data were pulled from the transcribed texts, coded, and analyzed using a systematic content analysis approach for categorizing questions asked by moderators. Initially, a preliminary category system (search-grid format) based on themes and questions from the interview guide was created. Next, transcripts were analyzed independently by two researchers to identify relevant key issues within each preliminary category. Thereafter, key findings were discussed within the research team to discuss whether a new code found during analysis should be added to the codebook, and the preliminary category system was adapted according to the nature of additional information not fitting into the initial category system. Next, all critical issues were labeled as codes, organized into main categories and subcategories. Each code was clearly defined and linked with samples from the transcriptions. Within our multiprofessional research team, all aspects were discussed and further modified until a consensus of the final category system was achieved. Final quotes included in this paper were edited for better clarity to remove potential errors produced in the original transcripts. No changes were made to the meaning of the quotes. Category labeling was performed using the NVivo version 12 software program (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia).

Results

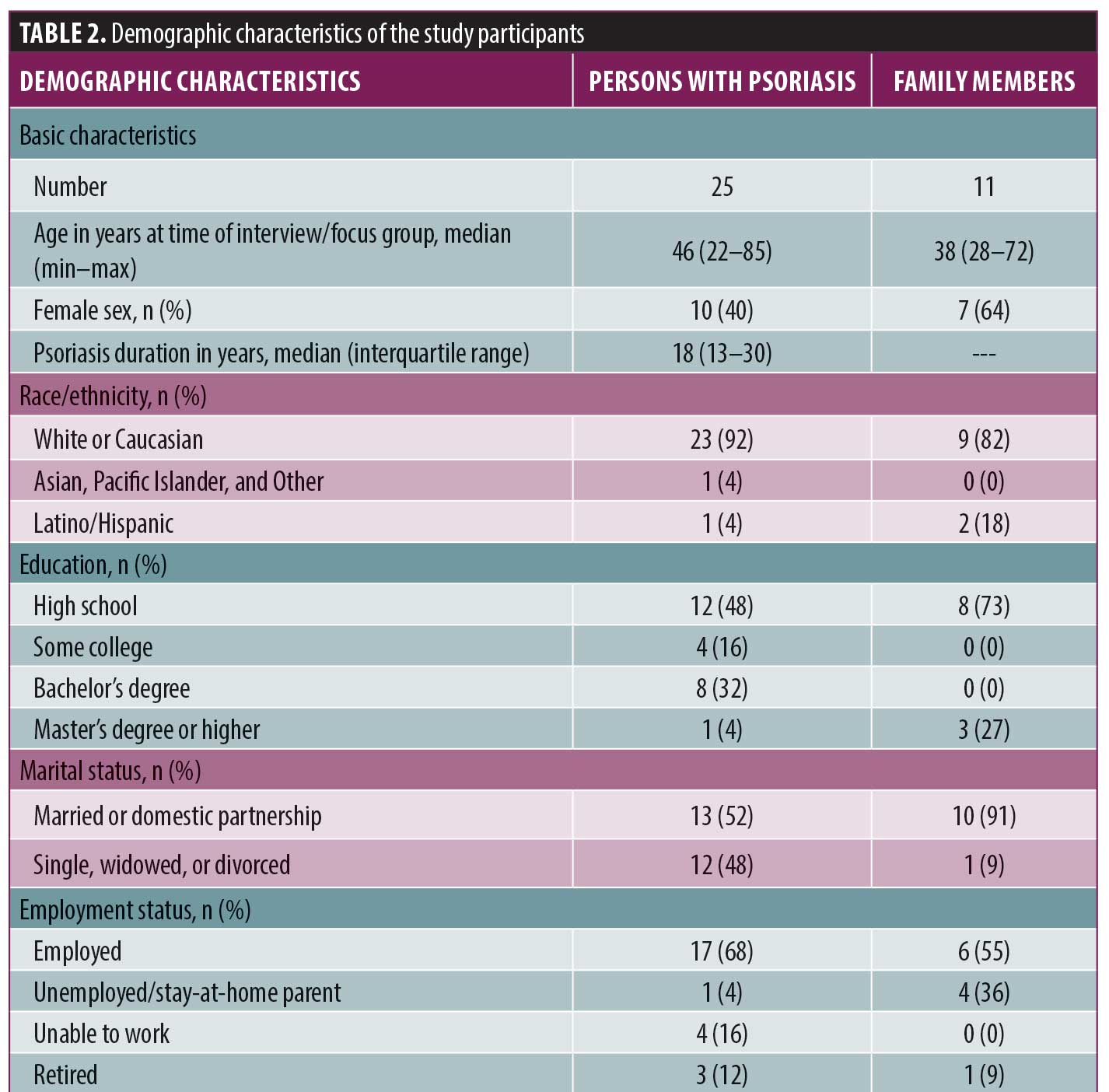

Ten interviews and five focus groups were conducted involving the 25 patients with psoriasis and 11 family members. Participants with psoriasis ranged in age from 22 to 82 years (median: 46 years) and relatives ranged in age from 28 to 72 years (median: 38 years) (Table 2). Ten participants with psoriasis identified as female and 15 identified as male, while seven family members identified as female and four identified as male. We found itchiness to be one of the most common and bothersome symptoms of active psoriasis. From the interview data, we identified three main categories/themes: 1) triggers of itchiness, 2) physical consequences of itchiness, and 3) prevention and treatment of itchiness.

Triggers of itchiness. Participants identified several factors that were perceived as exacerbators or triggers of itchiness, which we subcategorized into the following four themes: climate, self-care, lifestyle activities, and mental and behavioral (Table 3). Climate referred to arid conditions and hot weather, which both increased itchiness. Participants mentioned how moving to a state with high temperatures and low humidity, such as Utah, worsened the symptoms of their psoriasis: “Since I’ve been here, it’s been terrible because of the dry climate. When I lived in the East and the South, I didn’t have as big a problem because there’s so much moisture in the air, but this is terrible.” Constant indoor heating use during winters in the western United States leads to increased hot and dry indoor air, which can exacerbate the itchiness: “I think the winter is worse because you’re indoors more with the heaters going and the air is drier inside.”

The other three trigger subthemes related to activities of daily living. Participants recognized that normal daily activities of self-care, like bathing/showering, exacerbate their itchiness: “I’ve noticed it, like if I get out of the shower [and] it’s really dry, [my skin will] start to burn.” Fragrance-containing products, which are increasingly ubiquitous, were also identified as a trigger. Conversely, failing to persevere with a daily skincare routine also exacerbated itchiness.

For our participants, the simple act of getting dressed is not always so simple. Participants frequently altered their daily clothing choices to prevent itchiness, often at the expense of maintaining their style: “One of the things that drives me crazy is when I take off my socks at the end of the day and the itchiness goes. It’s really odd.” Certain fabrics (e.g., wool) aggravated the itchiness, so many participants chose natural cotton as their preferred fabric. Itchiness also interrupted patients’ ability to exercise, as exercise made them hot and sweaty, which led to itchier skin: “When I’d go to the gym or exercise or something like that, it’s like my scalp…or somewhere that I have spot on…is super itchy until I take the clothes off and take a shower.”

Regarding mental and behavioral triggers, emotional stress both caused and exacerbated itchiness as well as contributed to psoriasis flares. Many patients found that stress was associated with psoriasis flares and worsening itchiness: “When I’m stressed, I feel much more itchy.” In an attempt to relieve itching, patients frequently got caught in itch-scratch cycles, which could last for days.

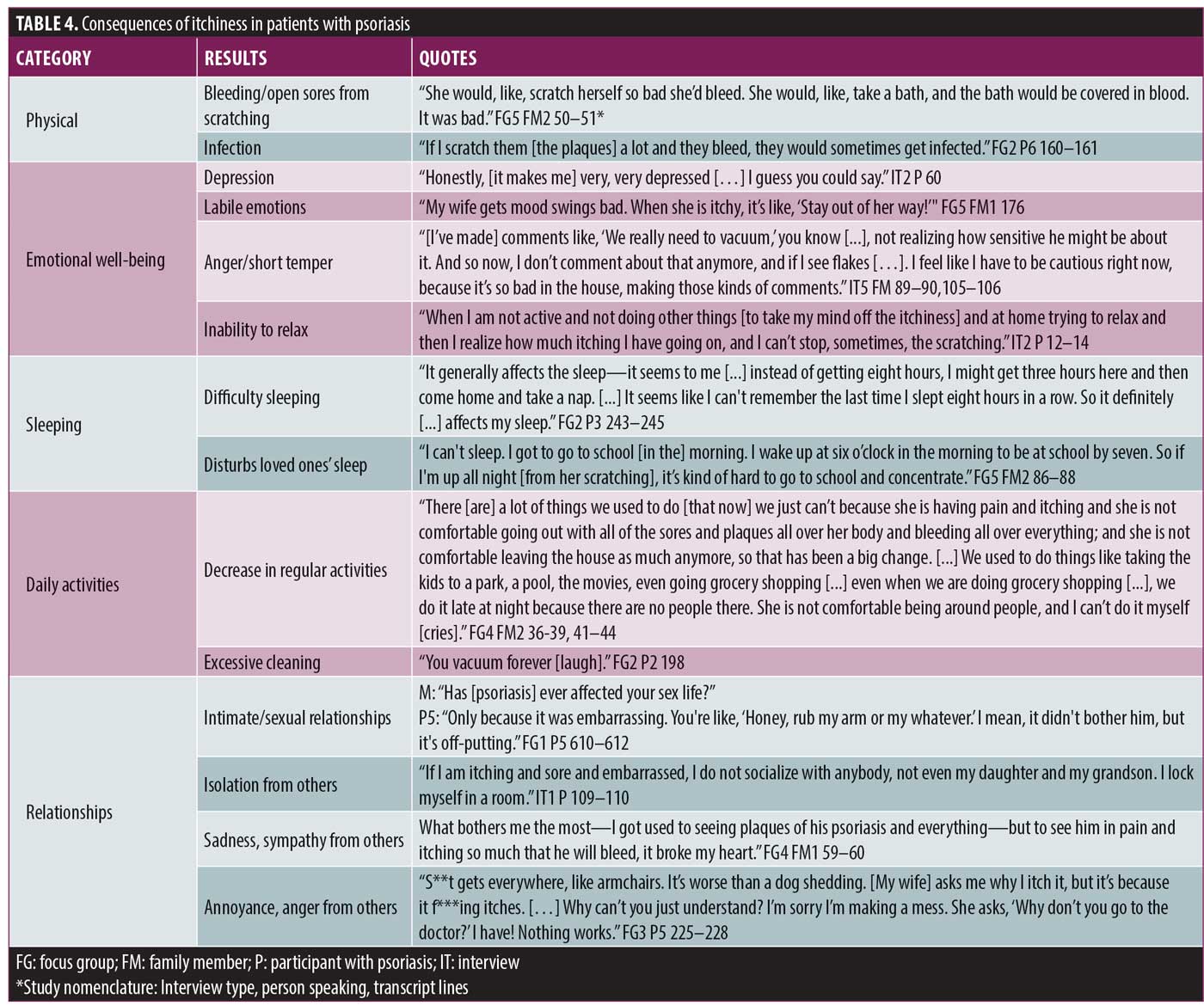

Consequences of itchiness. Participants commonly reported several reasons why their itchiness was so bothersome (Table 4). First, itchiness leads to physical damage. Scratching the itch often caused bleeding, flaking, and open sores; worsened existing wounds; and increased the chances of skin infection. Moreover, self-consciousness about blood-stained clothing and flakes everywhere as well as scratching in front of others all negatively influence emotional well-being, relationships, sleep, and daily activities.

Itchiness leads to mood instability, anger, and depression and prevents patients from relaxing. Family members reported that those with psoriasis would become much more sensitive to comments when they were itchy and were “unpleasant to be around.” Having a social life was an “uphill battle” for many of them. Some expressed frustration about a loved one’s criticism of their scratching, which psoriasis sufferers felt was out of their control: “S**t gets everywhere, like armchairs—it’s worse than a dog shedding. [My wife] asks me why I [scratch] it, but it’s because it f***ing itches. Why can’t you just understand? I’m sorry I’m making a mess. She asks, ‘Why don’t you go to the doctor?’ I have! Nothing works.”

To cope with embarrassment, several participants with psoriasis chose to isolate themselves and even avoid intimate relationships: “If I am itching and sore and embarrassed, I do not socialize with anybody, not even my daughter and my grandson. I lock myself in a room.” Patients and significant others both stated that, along with being self-conscious of active psoriasis on the skin, especially in the genital area, the physical discomfort and embarrassment from scratching decreased both the libido and frequency of sex. However, most family members were empathetic and supportive.

Itchiness not only limited or halted healthy social relationships but also restricted daily activities. Itchy psoriasis participants did not feel comfortable leaving the house; many stopped exercising, quit swimming or going to the gym, and did not enjoy being outdoors anymore. Other daily activities, such as laundry and vacuuming, became more frequent and time-consuming.

Those with more severe itchiness also had greater difficulty sleeping: “it seems to me, instead of getting eight hours [nightly], I might get three hours here and then come home and take a nap. And yeah, it seems like I can’t remember the last time I slept eight hours in a row.” Itchiness sometimes affected family members’ sleep as well. For example, a mother of a child with psoriasis stated that her daughter woke her up 3 to 4 times nightly screaming due to itchiness. Insomnia was common among those with severe itchiness and often disrupted planned daily activities. For example, a young man with psoriasis had difficulty sleeping and struggled with concentrating in school when he was itchy.

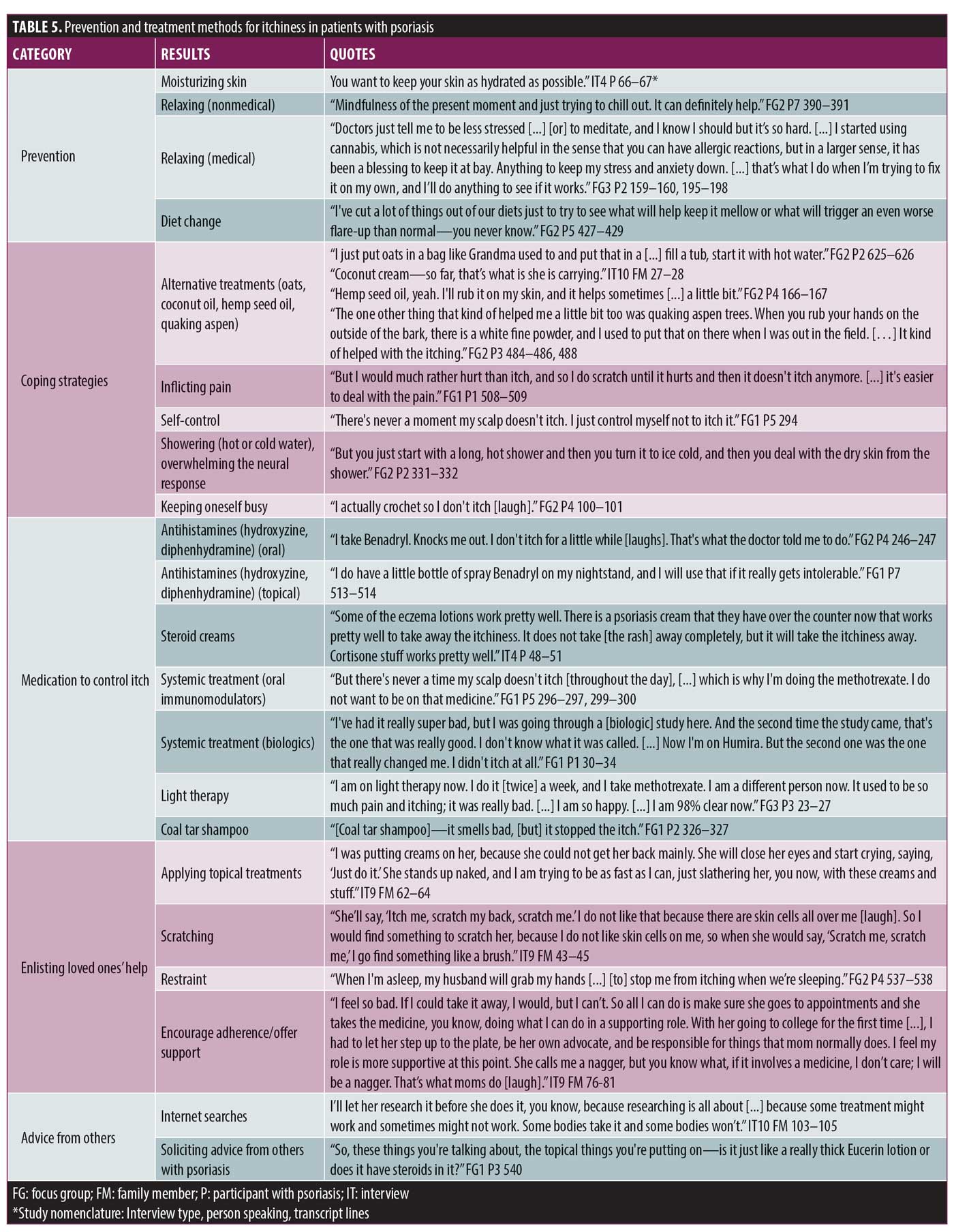

Prevention and treatment of itchiness. Several focus group participants highlighted the importance of preventative measures (Table 5). One strategy was consistency with a daily skincare routine of emollients throughout the day. Some started taking short showers/baths and changing to “natural” skin products to minimize the itchiness. Several individuals removed foods from their diets that they associated with flares and/or decided to follow a new diet to try to minimize symptoms. To cope with stress, mindfulness and anxiolytics were commonly employed.

Family members were frequently enlisted in psoriasis management to apply moisturizers and topical treatments in hard-to-reach places. When the affected family member was a child, itchiness greatly disrupted family dynamics, as that child needed extra attention, creating sibling jealousy and exacerbating sibling rivalry.

Those with psoriasis described taking individualized approaches to stop their itching. Several regularly scratched their skin until it was painful, because the symptom of pain was easier to deal with than itchiness. Others used extreme shower temperatures to overwhelm the nerves and control the itchiness. Participants listed topical moisturizing creams, oils (coconut or hemp seed), quaking aspen powder, topical steroids, topical antihistamines, and oat baths as useful in treating itchiness. Proactively managing their psoriasis was a common theme. Those with psoriasis described a willingness to “do anything” to decrease itchiness. Self-control techniques, occupying/distracting their hands, and covering the plaques (with clothing or wraps) were all mentioned as strategies. Oral sleep aids, such as oral antihistamines, were regularly used by some.

However, the best treatments for itchiness were prescription medications with success at clearing psoriasis, particularly systemic agents like biologics, oral immunomodulators, and light therapy. With treatment success, those with psoriasis frequently dichotomized their lives into times before and after effective treatment.

Discussion

Understanding the impact of itchiness and how it disrupts so many aspects in the lives of psoriasis patients is fundamental to providing effective patient-centered care. Our study was designed to provide dermatologists with an in-depth look at the degree to which itchiness disrupts the lives and relationships of those with psoriasis and their families. When we asked those with psoriasis what bothers them most about their disease, itchiness was the most frequently cited symptom. Indeed, itchiness affects 70 to 90 percent of patients with psoriasis,5–9 and relief from itchiness is a primary treatment expectation in patients with psoriasis.15

In our study, itchiness was described as a continuous state that fluctuates in intensity. In terms of triggers, climate (e.g., hot, dry weather), mental and behavioral factors (e.g., stress, self-induced itch–scratch cycle), lifestyle/activities (e.g., exercise, clothing), and self-care activities precipitate and exacerbate the itchiness. Identifying and avoiding triggers is a primary coping strategy for itchiness.

In addition, participants deal daily with the consequences of itchiness. We found that itchiness not only leads to physical damage of the skin but also negatively impacts patients’ emotional wellbeing, relationships, daily activities, and sleep. Remröd et al16 noted that patients with psoriasis and severe itchiness have high depressive scores. However, the relationship is unclear—does itchiness cause depression, or does depression increase the perception of itchiness?17 Sadness, anger, irritability, and emotional lability related to psoriatic itch were more commonly described in our study than depression was, but prior associations between these conditions have not been reported.

Prior work has shown that functional limitation and impaired social interactions are two of the most common concerns reported by patients with chronic itchiness18; however, little is known about how itchiness actually impairs these issues. We recorded physical and emotional reasons why patients experience functional limitation and social embarrassment related to itching. Patients reported itching causes the need to scratch often, visible skin flaking, blood-stained clothes, and mood instability and depression.

Sexual function and sexual desire decrease with more symptomatic psoriasis.8 Participants stated that, along with self-consciousness from the visual appearance of active psoriasis and its presence in the genital area, itchiness significantly decreased the libido and frequency of sex. Physical discomfort and embarrassment from scratching also led psoriasis patients to have a more restrictive social life.12,19

Eghlileb et al20 described how patients’ psychological distress might influence their loved ones’ emotions and increase relationship stress. Their study focused on the disruption of family members’ social lives due to the patient’s embarrassment of having psoriasis and the time demands related to self-care.20 While none of our participants expressed these concerns, they described decreased social activity due to those with psoriasis having a negative attitude toward going out and concerns their loved ones had about them contracting an infection from contact with sick people.

Treating the symptoms is as important as treating the skin disease when discussing disease management. Participants were often desperate to find any treatment to alleviate itchiness. Several mentioned that rubbing or scratching produced temporary relief. However, scratching induces local inflammatory mechanisms, eventually exacerbates the itchiness, and induces new plaque formation.21 Others preferred to inflict pain on themselves, including extreme water temperatures, as a means of overwhelming the nerves to control itchiness. This behavior can be explained with neurobiology, as itch appears to be under tonic inhibitory control of pain-related signals.22

Among the medications used to control itchiness, topical steroids and oral antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine) were commonly used. Topical corticosteroids inhibit cytokine activation, decreasing local inflammation and indirectly controlling itchiness23; however, their effectiveness varied in our participants. The introduction of biologic medications for psoriasis was the most life-changing factor participants and family members noted for curbing itchiness, similar to as seen in prior reports.24,25

The strengths of this study include a large sample for qualitative research, providing rich, in-depth insights for future clinical interventions and research directions. To collect a wide range of experiences, we included those with a broad range of disease severities as well as their significant others to gain several aspects of the disease’s impact. However, our study also has some limitations. Despite the range of patient and family member perceptions and experiences, the study population was recruited from a single tertiary center and might not offer the full diversity of views of a broader psoriasis population, including those with milder psoriasis or nonplaque psoriasis.

Conclusion

We found that itchiness negatively impacts the quality of life of both those with psoriasis and those with whom they live. In our experience, patients’ perception of itchiness is not routinely assessed in clinical practice. Often, only physician assessments of psoriasis severity (e.g., body surface area, psoriasis area, and severity index) are conducted during the clinical visit, which can result in suboptimal management when patient-reported and physician-reported outcomes differ.26–28 Evaluating and addressing the itchiness, quality of life impact, and psychological health of patients should be included systematically in daily practice to provide comprehensive care and improve the overall well-being of patients.29,30

References

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9(2): 136–139.

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003–2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(2):218–224.

- Choi J, Koo JY. Quality of life issues in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 Suppl):

S57–S61. - Bhosle MJ, Kulkarni A, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:35.

- Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, et al. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(3):280–284.

- Reich A, Hrehorow E, Szepietowski JC. Pruritus is an important factor negatively influencing the well-being of psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(3):257–263.

- Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Mediators of pruritus in psoriasis. Mediators Inflamm. 2007;2007:64727.

- Yosipovitch G, Goon A, Wee J, et al. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of pruritus among patients with extensive psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(5):969–973.

- Amatya B, Wennersten G, Nordlind K. Patients’ perspective of pruritus in chronic plaque psoriasis: a questionnaire-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(7):822-6.

- Sampogna F, Gisondi P, Melchi CF, Amerio P, Girolomoni G, Abeni D, et al. Prevalence of symptoms experienced by patients with different clinical types of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(3):594–599.

- Janowski K, Steuden S, Bogaczewicz J. Clinical and psychological characteristics of patients with psoriasis reporting various frequencies of pruritus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(7):820–829.

- Globe D, Bayliss MS, Harrison DJ. The impact of itch symptoms in psoriasis: results from physician interviews and patient focus groups. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:62.

- Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy: its current practice, implications and theory. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

- Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient-centeredness—a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107828.

- Gisondi P, Girolomoni G. Patients’ perspectives in the management of psoriasis: the Italian results of the Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) survey. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(5):390–393.

- Remrod C, Sjostrom K, Svensson A. Pruritus in psoriasis: a study of personality traits, depression and anxiety. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(4):439–443.

- van Laarhoven AI, Walker AL, Wilder-Smith OH, et al. Role of induced negative and positive emotions in sensitivity to itch and pain in women. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(2):262–269.

- Erturk IE, Arican O, Omurlu IK, Sut N. Effect of the pruritus on the quality of life: a preliminary study. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(4):406–412.

- Chen A, Beck KM, Tan E, Koo J. Stigmatization in psoriasis. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2018;3(3):100–106.

- Eghlileb AM, Davies EE, Finlay AY. Psoriasis has a major secondary impact on the lives of family members and partners. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(6):1245–1250.

- Bahali AG, Onsun N, Su O, et al. The relationship between pruritus and clinical variables in patients with psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(4):470–473.

- Paus R, Schmelz M, Biro T, Steinhoff M. Frontiers in pruritus research: scratching the brain for more effective itch therapy. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(5):1174–1186.

- Elmariah SB, Lerner EA. Topical therapies for pruritus. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30(2):118–126.

- Therene C, Brenaut E, Barnetche T, Misery L. Efficacy of systemic treatments of psoriasis on pruritus: a systemic literature review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(1):38–45.

- Mrowietz U, Chouela EN, Mallbris L, et al. Pruritus and quality of life in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: post hoc explorative analysis from the PRISTINE study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(6):1114–1120.

- Silva MF, Fortes MR, Miot LD, Marques SA. Psoriasis: correlation between severity index (PASI) and quality of life index (DLQI) in patients assessed before and after systemic treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(5): 760–763.

- Schafer I, Hacker J, Rustenbach SJ, et al. Concordance of the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and patient-reported outcomes in psoriasis treatment. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20(1):62–67.

- Takeshita J, Callis Duffin K, Shin DB, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for psoriasis patients with clear versus almost clear skin in the clinical setting. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(4):633–641.

- Secrest AM, Chren MM, Hopkins ZH, et al. Benefits to patient care of electronically capturing patient-reported outcomes in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(4): 826–827.

- Gaufin M, Hess R, Hopkins ZH, et al. Practical screening for depression in dermatology: using technology to improve care. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(3):786–787.