J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(2):61–67.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(2):61–67.

by Eman Elmorsy, PhD; Nouran Aboukhadr, PhD; Maha Tayyeb, MS; and Alsayeda A.A. Taha, PhD

All authors are with the Faculty of Medicine at University of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background: A number of treatments have been used to treat melasma, with varying degrees of success and side effects.

Objective: We sought to compare the efficacy of a single session of low-power fractional CO? (10,600 nm) laser followed by Jessner’s solution peeling against that of Jessner’s solution peeling alone for the treatment of melasma by way of a prospective cohort comparative study performed at Alexandria Main University Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt. This study included 40 Egyptian female patients diagnosed with melasma. Group A received a single session of low-power fractional CO? laser followed by Jessner’s solution peeling for up to six sessions, while Group B received up to six sessions of Jessner’s solution peeling alone. Responses were evaluated using the modified Melasma Area and Severity Index (mMASI) score.

Results: There was a statistically significant (p?0.001) difference between mMASI score between before and after treatment in both groups. There was no intergroup significant difference in mMASI score improvements.

Conclusion: Both low-power fractional CO? laser combined with Jessner’s solution and Jessner’s solution peeling alone were safe and effective for the treatment of melasma in patients with different skin types, especially in dark skin types (Fitzpatrick Skin Types III and IV).

KEYWORDS: Melasma, fractional laser, Jessner’s solution

Melasma, a term derived from the Greek word melas, meaning black, is a common acquired circumscribed hypermelanosis of sun-exposed skin. It is most commonly located on the forehead, cheeks, upper lips, and chin, but other photoexposed sites can be involved.1

The most important epidemiological correlation is between melasma and sex, as women are at 7 to 9 times greater risk of developing melasma relative to men.2 Other strong links are suggested between melasma and pregnancy, oral contraceptive intake, and darker skin phototypes (Fitzpatrick skin types III–IV).3–5 The etiopathogenesis of melasma is complex and not completely understood. It results from an interplay of several internal and external factors. Among these factors, genetic predisposition, sun-exposure, and hormonal factors are the most important ones.6 Sanchez et al7 used Wood‘s light findings to classify melasma into three different types: epidermal, dermal, and mixed.

Various treatments, including topical depigmenting agents, chemical peels, dermal abrasion, and different types of laser therapy, have been used to treat melasma, with varying degrees of success and side effects.8 The aim of the present study is to compare the efficacy of Jessner’s peel in combination with a single session of low-power fractional CO? (10,600nm) laser versus Jessner’s peel alone for the treatment of melasma.

Methods

Study population and design. This was a prospective, single-blinded, randomized, comparative study. It included 40 Egyptian women who had been diagnosed with melasma and recruited from the outpatient clinic of Alexandria Main University Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt. Written informed consent was obtained and the study protocol was approved by the institution’s ethics committee prior to participant enrollment in the study.

Patients were randomly assigned into two age-matched groups using a closed envelope method. Female patients with Fitzpatrick Skin Types II through IV and aged 20 to 60 years were included in this study. Group A included 20 women who underwent a single session of low-power fractional CO? (10,600nm) laser followed by Jessner’s solution peeling after two weeks for up to six sessions. Group B included 20 women who underwent Jessner’s solution peeling for up to six sessions at biweekly intervals.

Jessner’s solution was prepared as a mixture at the same laboratory of the following constituents; resorcinol (14g), lactic acid (14g), and salicylic acid (14g) in 95% ethyl alcohol (sufficient quantity to make 100mL).

Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, active herpetic lesions or any concurrent active skin disease within the treated area, photosensitive skin conditions such as systemic lupus erythematous, a history of intake of phototoxic drugs, tendency to develop hypertrophic scars or keloids, and the usage of any treatment related to melasma lesions one month prior to the study.

Study protocol. We collected a full medical history from each participant, including age, drug history (especially oral contraceptive pills or phototoxic drugs), gynecological history, history of endocrine dysfunction, history of exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR), use of cosmetics, duration and progression of melasma and previous treatments, and history or tendency to develop hypertrophic scars or keloids. All participants also underwent a local examination under natural light to confirm the diagnosis of melasma and Wood’s light examination to determine the type of melasma (i.e., epidermal, dermal, or mixed). Wood’s light causes intensification of pigmentation in epidermal-type melasma, but does not enhance the pigmentation in the dermal type. A combination of epidermal and dermal macules is recognized as the mixed type. Finally, modified Melasma Area and Severity Index (mMASI) scores were calculated9 and digital photographs using the same positioning, lightening, and camera settings in all cases were taken.

Treatment procedure. In Group A, anesthesia was achieved with topical 30% lidocaine gel for an hour prior to the laser session. Then, a fractional CO? (10,600 nm) laser session using SmartXide Dermal Optical Thermolysis (DOT, DEKA, Calenzano, Italy) at settings of 6 W and 900?m pitch for 1,000?s was completed. Patients were instructed to apply corticosteroid cream immediately posttreatment followed by a few days of the application of a bland emollient. They were advised to strictly avoid sun exposure and to apply a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 50+. Jessner’s peeling sessions were started two weeks after the laser session and patients were subjected to up to six treatment sessions at biweekly intervals.

In Group B, after drying of the face, degreasing was performed with alcohol-soaked cotton pieces to remove all cutaneous oils, and Jessner’s solution was applied in a uniform coat to the whole face, avoiding the angles of the eyes and mouth, using two cotton-tipped applicators for accurate application. Neutralization was achieved with water followed by topical steroid application. Patients were advised to use bland emollient twice daily for one week following the session, to strictly avoid sun exposure, and to apply a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 50+. Peeling sessions were performed every two weeks, unless erythema, folliculitis or peeling abrasions occurred. Peeling sessions were stopped after a maximum of six sessions or the clearance of melasma.

Evaluation and follow-up. The evaluation of each patient by two independent blinded dermatologists was performed by mMASI score calculation and the assessment of standardized digital photographs taken at baseline, each treatment session, at the end of treatment, and finally at the end of the follow-up period of six months. The digital photographs were scored as -1=worse, 0=no change, 1=poor (1%–24% improvement in melasma), 2=good (25%–49% improvement in melasma), 3=marked (50%–74% improvement in melasma), or 4=excellent (75%–100% improvement in melasma).10 Patient-reported outcome satisfaction was assessed using the same score. Recording of side effects was completed every session by asking the patient if there was any problem that had appeared since the last session and observing whether it was still present.

Statistical analysis. Data were fed into the computer and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 software program. Qualitative data were described using numbers and percentages, while quantitative data were described using range (minimum and maximum), mean, standard deviation, and median values. Comparison between different groups regarding categorical variables was tested using the chi-squared test. When more than 20 percent of the cells had an expected count of less than 5, the correction for the chi-squared test was conducted using Fisher’s exact test or Monte Carlo correction. If the data were abnormally distributed, nonparametric tests were used. For abnormally distributed data, comparisons between two independent populations were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level.

Results

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding age (p=0.542). A comparison of the skin phototypes of participants is shown in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of skin type (p=0.560). A comparison of the two groups according to obtained history is shown in Table 2. Melasma duration was a mean of 8.66±5.68 years (range: 3 months–20 years) in Group A and 7.40±4.59 years (range: 2–15 years) in Group B. There was no statistical significant difference between the groups regarding the duration of melasma (p=0.514). The most common type of melasma seen during Wood’s light examination in both groups was the epidermal type (60% in Group A, 65% in Group B) followed by the mixed type (25% in each group) and dermal type (15% in Group A, 10% in Group B). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding the type of melasma.

The calculation of mMASI scores indicated the mean mMASI score in Group A was 6.01±4.51 points, while that in Group B was 4.42±3.89 points. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding mMASI score (p=0.192).

A comparison of the two studied groups according to response of the participants to treatment is shown in Table 3. There was a statistically significant improvement in melasma in both groups, with no intergroup statistically significant difference. A comparison between the two groups regarding the percentage of improvement in relation to the number of treatment sessions is shown in Figure 1 with an intergroup statistically significant difference (p=0.015).

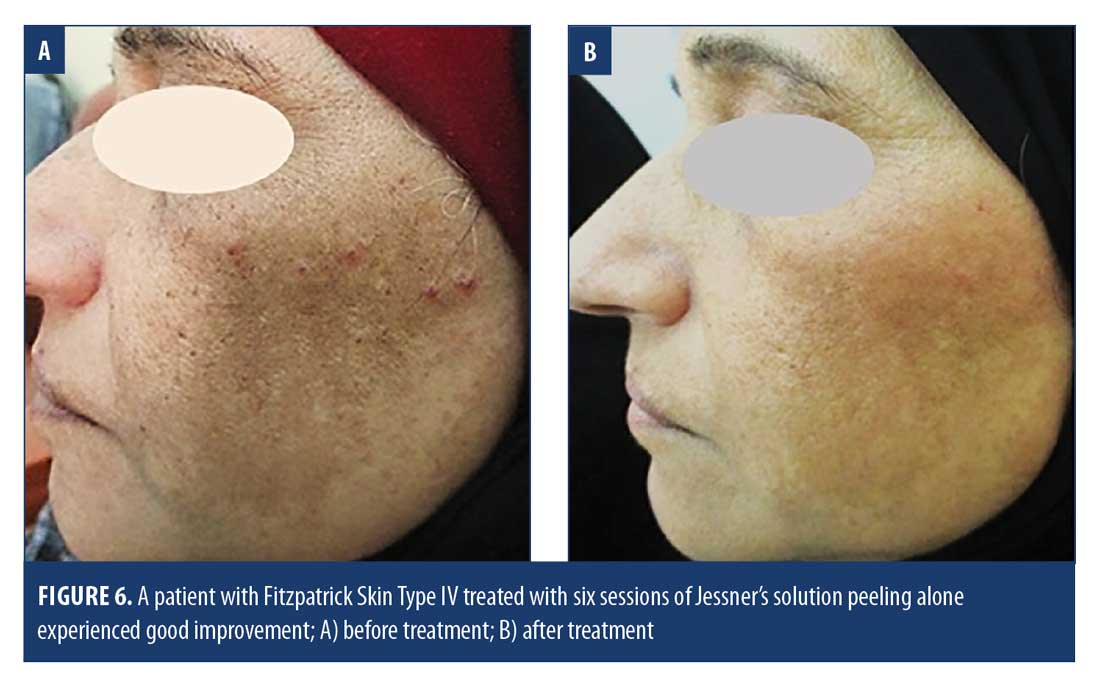

A comparison of mMASI scores before and after treatment and at the end of follow-up between both groups revealed that the mean mMASI score in Group A was reduced from 6.01±4.51 points before treatment to 3.09±4.06 points after treatment, while, at the end of the six-month follow up, the mean mMASI score was 4.22±4.26 points. In Group B, the mean mMASI score was reduced from 4.42±3.89 points before treatment to 2.01±2.07 points after treatment and, at end of follow-up, it was 2.69±2.46 points, indicating a statistically significant reduction in mMASI score at the end of treatment in both groups with a slight elevation in the mMASI score occurring by the end of the follow-up period. However, a statistically significant reduction was still maintained (Figure 2). Figures 3–6 present some clinical photographs of patients in both groups.

A comparison of mMASI scores before and after treatment and at the end of follow-up between both groups revealed that the mean mMASI score in Group A was reduced from 6.01±4.51 points before treatment to 3.09±4.06 points after treatment, while, at the end of the six-month follow up, the mean mMASI score was 4.22±4.26 points. In Group B, the mean mMASI score was reduced from 4.42±3.89 points before treatment to 2.01±2.07 points after treatment and, at end of follow-up, it was 2.69±2.46 points, indicating a statistically significant reduction in mMASI score at the end of treatment in both groups with a slight elevation in the mMASI score occurring by the end of the follow-up period. However, a statistically significant reduction was still maintained (Figure 2). Figures 3–6 present some clinical photographs of patients in both groups.

There was an inverse correlation between the percentage of reduction in the mMASI score after treatment and the duration of melasma in Group B (rs=-0.590), but there was no correlation in Group A. Patient satisfaction was higher in Group A; however, this may be attributed to the rapid initial response.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the majority of cases were of Fitzpatrick Skin Type III (57.5%), followed by of skin type IV (25%). This finding was in accordance with a study by El Garem et al,11 which included 30 Egyptian women with skin types III (63%), II (20%), IV (10%), and V (7%). In a study by Sharquie et al,12 who assessed 30 patients at Baghdad Hospital, found that skin type IV was the most common among participants (87.5%), followed by skin type V (8.33%), and skin type III (4.17%).

The present study found that a history of facial hair removal by threading was the most common predisposing factor related to melasma (77.5%), followed by a history of excessive ultraviolet radiation exposure (67.5%), while a history of pregnancy was found in 57.5 percent of patients, followed by an intake of oral contraceptive pills and a positive family history for melasma (32.5% and 20%, respectively).

Similarly, a study by Guinto et al,4 which included 188 Tunisian women, reported the same previous triggering factors for melasma. Specifically, it recorded regular removal of unwanted facial hair in 56 percent, sun exposure as a triggering factor in 51 percent, pregnancy as an aggravating factor in 51 percent, and oral contraceptive use in 38 percent of study participants. On the contrary, the study by Handel et al13 that evaluated 207 women with melasma and their controls in Brazil reported a history of pregnancy in 79 percent of cases, followed by a family history of melasma in 61 percent of cases. Meanwhile, ultraviolet radiation exposure and oral contraceptive pills intake were detected in 26 percent and 10 percent, respectively.

Our study showed that the epidermal pattern was the most common pattern of melasma, which was observed in 62.5 percent of participants, followed by the mixed pattern (25%) and the dermal pattern (12.5%). This finding was in agreement with the study by Jalaly et al14 which included 40 Iranian women and observed the epidermal pattern as the most common pattern of melasma (55%), followed by the mixed pattern (22.5%) and dermal pattern (12.5%).

Different studies have been conducted on different modalities for the treatment of melasma. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published data comparing fractional CO? laser and Jessner’s solution peeling in the treatment of melasma.

The current study found that participants in Group A (CO? laser with Jessner’s solution peeling) experienced marked to good improvement (75% marked, 15% good), while five percent reported excellent improvement and five percent reported poor response.

We also found that 36.8 percent of patients experienced initial improvement after one session of CO? laser. There was a statistically significant reduction in mMASI score after treatment. However, a slight elevation in the mMASI score occurred at the end of the follow-up period.

A study by Nouri et al15 that included eight patients in Florida compared the effects of pulsed CO?laser alone and in combination with Q-switched alexandrite laser and reported that all patients in both treatment groups showed complete resolution of melasma in the treatment area. Their study also noted that the efficacy of CO? laser alone in removing pigmentation was less than that of combined CO? and Q-switched alexandrite laser.

A split-face study by Jalaly et al14 that included 40 female patients in Tehran compared five sessions of low-power fractional CO? laser application versus low-fluence 1,064-nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser for the treatment of melasma. The results showed that the reductions in Melanin Index (MI) and mMASI scores for the fractional CO? laser-treated side were significantly greater than those for the 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Complete improvement was detected in 62.5 percent of patients treated by fractional CO? laser versus 15 percent in the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser group. The efficacy of fractional CO? laser in reducing the MI score was statistically significant in the patients with epidermal and dermal melasma relative to the to the 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser.

Our study reported that participants in Group B (treated with Jessner’s solution alone) showed marked to good improvement (60%marked, 25% good) with 10 percent reporting excellent improvement and five percent reporting poor response. We also found that 45 percent of patients experienced improvement after the full six sessions of Jessner’s solution peeling. There was a statistically significant reduction in mMASI score after treatment. However, a slight elevation occurred by the end of the follow-up period. There was no statistically significant correlation between the reduction in mMASI scores and skin type but there was a statistically significant greater improvement in patients with epidermal melasma than dermal melasma and there was an inverse correlation between the percentage of reduction in mMASI scores following treatment and the duration of melasma in Group B. These findings are in agreement with a study by Azzam et al,16 which compared six weekly trichloroacetic acid (TCA) 20% peels with Jessner’s solution peels and a topical regimen of hydroquinone 2% and kojic acid at bedtime in 45 patients with epidermal and mixed melasma. All groups demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in MASI scores (p<0.001) that was maintained after 12 weeks of follow-up. The TCA peel group showed the greatest decrease in MASI scores (p=0.01).

Lee et al17 studied the therapeutic effect and adverse effects of Jessner’s peel when combined with 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser versus 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser plus placebo in 52 Korean patients with melasma. Patients received 10 sessions of 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser plus chemical peeling with Jessner’s peel in a two-week interval and showed a statistically significant reduction in mMASI scores, including a greater reduction in mMASI scores in those with the dermal type of melasma. This study suggested that Jessner’s peel is a safe and effective method in the early course of treatment for melasma when combined with low-fluence 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser.

A study by Abdel-Meguid et al18 included 24 Egyptian women (skin prototypes IV–V) with bilateral melasma and compared the safety and efficacy of combined TCA (20%–25%) and Jessner’s solution versus TCA (20%–25%) alone. Patients were treated for six sessions at two-week intervals in a split-face pattern. Right and left sides were randomly allocated to receive either combined peeling with Jessner’s solution and TCA 20% to 25% or TCA 20% to 25% alone. After treatment, both therapeutic modalities showed significant decreases in MASI scores. In addition, MASI scores after treatment were significantly lower on the side treated with the combination of Jessner’s solution and TCA than the side treated with TCA alone. There were statistically significant negative correlations between the percentage of improvement and the duration of melasma.

A study by Safoury et al19 compared the therapeutic effect of combined 15% TCA and modified Jessner’s solution with 15% TCA alone on 20 Egyptian women with skin types III and IV. In this study, 15% TCA was applied to the whole face, with the exception of the left malar area, to which TCA 15% and modified Jessner’s solution were applied instead. A 54 percent decrease in MASI scores in the right malar area (TCA 25% treated) at the end of treatment relative to a 71 percent decrease in those for the left malar (treated by TCA 15% and Jessner’s solution) area was recorded, while a 49 percent decrease in MASI scores in the right malar area as compared with to 61 percent decrease in MASI scores in the left malar area was also apparent—denoting a statistically significant improvement in melasma when combining TCA 15% with Jessner’s solution relative to the use of TCA 15% alone.

A study by El Garem et al11 included 30 Egyptian women and compared the modified Jessner’s solution and glycolic acid 70% on a split-face basis at two-week intervals with a maximum of eight sessions. The authors found a statistically significant greater reduction in the total MASI score in the modified Jessner’s solution–treated side than in the glycolic acid–treated side. However, patients with skin type III experienced a significant reduction in the MASI score in the modified Jessner’s scolution–treated side as compared with for the glycolic acid-treated side.

A study by Ejaz et al20 included 60 Pakistani patients with epidermal melasma, who were divided into two groups to compare the effects of Jessner’s solution and 30% salicylic acid treatment for 12 weeks at two-week intervals. The authors reported a reduction in MASI scores in both groups and suggested that both treatments were equally effective and safe in Asian skin.

Regarding the safety and side effects after treatment, our study reported that all patients experienced burning sensation during and after Jessner’s solution application, which subsided within the following weeks. No other complication was reported. The only adverse event that occurred after laser treatments was mild pain.

These results are in accordance with those of many previous studies, such as the study by Lee et al,17 who examined the therapeutic and adverse effects of Jessner’s peel in combination with 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser and 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser plus placebo in patients with melasma. Here, the authors noted that four patients experienced burning sensation during and after Jessner’s solution application and mild pain and erythema after laser treatment, respectively. The study by Jalaly et al14 that compared low-power fractional CO? laser and low-fluence 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser for the treatment of melasma reported that patients treated with low-power fractional CO? laser were more satisfied and experienced a lower rate of side effects. The study by Nouri et al5 found that two out of four patients (50%) had peripheral hyperpigmentation in the group treated by CO? laser only, while no patients (0%) in the group treated by CO? laser and alexandrite laser group showed this phenomenon.

Abdel-Meguid et al18 reported in their study that participants experienced discomfort on the side treated with modified Jessner’s solution in combination with TCA 15% (80%) compared to the side treated with TCA 15% alone (20%). Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation developed only on the side treated with 15% TCA alone in 10% of patients.

Conclusion

Our study found that low-power fractional CO? laser in combination with Jessner’s solution peeling and Jessner’s solution peeling treatment alone were both safe and effective for the treatment of melasma in patients with different skin types, especially Fitzpatrick Skin Type III. However, the group that received treatment using combined fractional laser and Jessner’s solution experienced more rapid improvement and higher patient satisfaction. Both groups experienced some recurrence of melasma at the end of the follow-up period, which emphasizes that melasma is a lifelong problem that requires continuous management.

References

- Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Dash S. Pigmentary disorders in India. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25(3):343–352.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. Pigmentary disorders: an insight. Pigment Int. 2014; 1(1):5–7.

- Ortonne JP, Arellano I, Berneburg M, et al. A global survey of the role of ultraviolet radiation and hormonal influences in the development of melasma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(11):1254–1262.

- Guinot C, Cheffai S, Latreille J, et al. Aggravating factors for melasma: a prospective study in 197 Tunisian patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(9): 1060–1069.

- Perez M, Luke J, Rossi A. Melasma in Latin Americans. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(5): 517–523.

- Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Katsambas A. Hyperpigmentation and melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6(3):195–202.

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, et al. Melasma: a clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4(6):698–710.

- Rendon M, Berneburg M, Arellano I, Picardo M. Treatment of melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 Suppl 2):S272–S281.

- Pandya AG, Hynan LS, Bhore R, et al. Reliability assessment and validation of the Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) and a new modified MASI scoring method. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 64(1):78–83.

- Fabi SG, Friedmann DP, Niwa Massaki AB, Goldman MP. A randomized, split-face clinical trial of low-fluence Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (1,064 nm) laser versus low-fluence Q-switched alexandrite laser (755 nm) for the treatment of facial melasma. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46(7):531–537.

- El Garem YF, Mahmoud HA, Kamel MN. Safety and efficacy of modified Jessner’s solution versus 70% glycolic acid for the treatment of melasma in different skin types: a split-face study. J Egyptian Women Dermatol Soc. 2014;11(3):159–166.

- Sharquie KE, Al-Tikreety MM, Al-Mashhadani SA. Lactic acid chemical peels as a new therapeutic modality in melasma in comparison to Jessner’s solution chemical peels. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(12):1429–1436.

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(3): 588–594.

- Jalaly N, Valizadeh N, Barikbin B, Yousefi M. Low-power fractional CO? laser versus low-fluence Q-switch 1,064 nm Nd:YAG laser for treatment of melasma: a randomized, controlled, split-face study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15(4):357–363.

- Nouri K, Bowes L, Chartier T, et al. Combination treatment of melasma with pulsed CO? laser followed by Q-switched alexandrite laser: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(6): 494–497.

- Azzam OA, Leheta TM, Nagui NA, et sal. Different therapeutic modalities for treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(4):275–281.

- Lee DB, Suh HS, Choi YS. A comparative study of low-fluence 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with or without chemical peeling using Jessner’s solution in melasma patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25(6):523–528.

- Abdel-Meguid AM, Taha EA, Ismail SA. Combined Jessner solution and trichloroacetic acid versus trichloroacetic acid alone in the treatment of melasma in dark-skinned patients. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(5):651–656.

- Safoury OS, Zaki NM, El Nabarawy EA, Farag EA. A study comparing chemical peeling using modified Jessner’s solution and 15% trichloroacetic acid versus 15% trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009; 54(1):41–45.

- Ejaz A, Raza N, Iftikhar N, Muzzafar F. Comparison of 30% salicylic acid with Jessner’s solution for superficial chemical peeling in epidermal melasma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18(4):205–208